Christian Windler had given me a couple of leads and introduced me to the weird world of cybernetics, but, aside from the possibility of the nefarious involvement of project MKUltra, I wasn’t much further along in terms of discovering the origins of the Polybius legend.

Next was to check out reports of similar games. In this regard, as mentioned in section 1, there are two major contenders: Tempest and Poly Play. Despite the fact that Tempest does have a vector monitor, which Windler considers a sine qua non for a video game that can ‘interface’ with human consciousness in the manner he would expect, it just didn’t feel right. Tempest was a very popular game in its time; it seems weird to me that something this dark would be tested on a game cabinet that would go on to enjoy great commercial success. Further, the reports of epileptic reactions to the game seemed to doom the Tempest approach to the world of the prosaic; at best, I’d maybe be able to prove that the Polybius story is just a wild and silly overreaction to something totally mundane. Where’s the fun in that, even if it’s true?

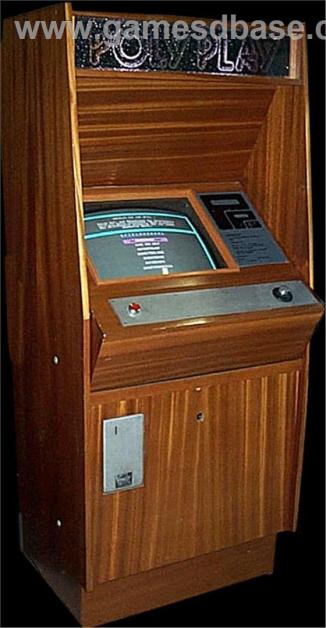

So let’s take another look at Poly Play.

Aw yeah, that’s the stuff.

Poly Play was developed in 1985 by a company called VEB Polytechnik. As the only video game in communist East Germany, it was something of a dangerous necessity. Video games, in one sense, were seen as a symbol of American fruitless time-wasting and commercialism— the antithesis to the Soviet ideals of hard work and productive, positive social engagement. At the same time, living conditions in East Germany were awful, and the government offered certain diversions to its populace as an aid to keeping the peace. Poly Play cabinets were produced in large numbers and installed primarily in youth hostels and non-profit clubs, where they enjoyed great popularity.

Poly Play was actually eight games in one, hence the name. There was Hirshjagd, a hunting game, Hase und Wolf (‘Hare and Wolf’) a Pac-Man clone, Abfahrtslauf, a skiing game not unlike Skifree, for those of you who remember that one, Schmetterlinge, in which the object is to catch butterflies, Schießbude, another shooter, Autorennen, a racing game, Merkspiel, a tile-based memory-testing game, and Wasserrohrbruch, in which the player collected droplets in a bucket to keep a room from flooding. According to the reviews I’ve found, the games were pretty subpar overall, though I guess when you’re the only video game around you don’t necessarily need to be that great to pass muster.

What we’re concerned with here, if we’re going on the assumption that Poly Play may be the seed of truth which sprouted in the American consciousness as Polybius, is the inner workings of the game. This is where you’d find whatever hidden weirdness lay under the surface of the accursed arcade game. Poly Play ran on a 2.5mHz Russian CPU (already long obsolete in the West when the game was created) and used a (sigh) raster display, in fact actually just a straight-up German television set which was mounted inside the wood-grain cabinet, on hinges so it could be lifted away to expose the game’s innards.

One of the cabinets found its way to a retro arcade business in Oakland, California, called Andy’s Arcade; from the website, it appears to be a kind of museum / collector’s store, and their section on their Poly Play cabinet is quite extensive, for which I am thankful. The exterior of the game was like a well-constructed piece of furniture, everything bolted sturdily together and designed to allow easy maintenance and cleaning. When the cabinet was opened up, however, things started to get weird.

First, the entire interior area of the machine was lined with reflective metallic foil. There seems to be no practical purpose for this; the foil would have prevented easy dispersal of heat, and while a 2.5mHz processor and a smallish TV certainly don’t produce an awful lot of heat, it’s at least a minor factor to be considered in the cabinet construction, particularly since the foil doesn’t seem to serve any purpose. One possibility is that the foil was put there to reflect radio-frequency emissions, keeping them from leaving the cabinet. It would be useful for that, but then what kind of video game produces RF to the degree that it would need special shielding to keep it from interfering with other electronics? Could this be a side-effect of whatever technology had been causing the effects reported regarding Polybius? (On the other hand, in my research, it took an actual former East German resident to suggest what is certainly the distinctly realistic possibility that the shielding was to stop the game from interfering with hidden microphones planted by the government.)

As for the display, everything there seemed to be on the up-and-up. With no vector display, the flash-rate factor that Windler argues is necessary for a software-brain interface is not present. However, remember that the Polybius mythos doesn’t suggest that a full-on man-machine mind-meld happened, merely that the game had negative psychological and physiological effects upon the player. We don’t necessarily have to find evidence of something as sophisticated as Windler was describing.

Let’s forget the actual game display for a moment. The cabinet also has what Andy’s Arcade calls a ‘light organ’, a series of light-bulbs in a display at the top of the cabinet, behind a glass cover inscribed with the game’s name. Other cabinet designs (there were several) have an extra strip of coloured lights just above the game display.

Presumably, these were meant to increase the game’s visibility in a dimly-lit room; displays like this were common on arcade games. However, while these displays would normally be hooked to the game’s power source, the light organs on Poly Play were connected directly to the CPU. This is totally unnecessary; the necessary light display can be produced by simple wiring alone, without the intervention of a computer chip (blinking lights on a Christmas tree, for instance, don’t have a processor). The only reason you’d need to connect the light organ to the processor is if the gameplay changed the light display (which it doesn’t) or if the lights had special programming based on calculated variables. In short, something about the display produced by that light organ has to be a lot more complicated than it seems. Is it possible that the game itself is a mere diversion, something to keep somebody occupied in the optimal viewing position for long enough for the psychological effects of the light organ to take effect?

Andy’s Arcade has helpfully provided a short video clip of the light organ in action. One morning after work (I work graveyard shifts) I decided to put this ~1-second clip on a fullscreen loop and watched it intently for ten minutes straight. I started at 0842AM; by 0844 I was starting to feel a little nauseated. At 0846, the mild headache I’d had for the past few hours suddenly became noticeably more painful, and at 0847 I started to notice very minor peripheral hallucinations; specifically, it seemed like objects in the background of the video had moved within the frame over the course of several loops. Over the next few minutes, I saw greyish shapes in the corner of my eyes that vanished when I looked at them, and at one point I could have sworn I heard someone whisper my name. Somewhere around then I zoned out completely, losing track of time, such that my ten-minute experiment stretched to twelve minutes. By 0854, when I snapped back to my senses and shut off the video, my head was pounding, my guts seemed tied in knots, and I had a profound, thick-headed feeling of confusion, so intense that it took me another two minutes to remember the word ‘confusion’ so I could write it into my notes.

“What’s it like, Bart? Bart? Bart?”

Now, who knows. My physical state probably wasn’t ideal for an unbiased test; I’d just gotten home from a night at work, I was over-caffeinated, probably dehydrated, and I hadn’t had anything to eat. All of that could easily produce nausea and a headache without necessarily requiring sinister technological intervention. As for the confusion and peripheral hallucinations, that’s probably par for the course when you spend ten minutes staring at brightly-flashing lights. I went to bed that morning hoping for a terrible nightmare, to cap off the symptoms list, but I slept like a baby. So it’s probably psychosomatic. Maybe you should try it yourself to be sure. DO NOT DO SO IF YOU ARE EPILEPTIC.

The light organ angle aside, there are other weird, circumstantial connections between Polybius and Poly Play. As mentioned before, the control system is identical (one joystick, one button) and the Poly Play cabinet would look a lot like that grainy photo of the Polybius cabinet if you just painted it black. Poly Play, good communist technology that it was, was designed to be easily switched between a free-to-play mode and another mode that took money through a coin slot. The payment option on many of the machines would be turned on or off basically at the owner’s discretion; this may explain the fact that many Polybius players have claimed that the game often didn’t require payment— you’d just walk up to the cabinet and it’d be ready to go. And as you’d expect from a free arcade game which was also the only arcade game, lines of people waiting for a round of Poly Play often grew to an unmanageable size; this might be the foundation of memories of Polybius’s addiction-like popularity.

Oh, yeah: there’s also the fact that Poly Play was produced by the fucking Stasi!

Pictured: Not a video game company logo.

According to a Google translation of this website, “The development of Polyplay was curiously initiated by the Ministry of State Security (the East German secret service). About whose motive can only speculate: it is conceivable that it was about to break down desires to appropriate Western products in the population.“ The cabinets themselves were government property, and they were installed by Stasi agents on request, after the proprietor of a suitable establishment applied for and received a special permit.

The Stasi pioneered the technique, later adopted by the secret polices of other Eastern Bloc countries, of using extensive psychological harassment against their enemies. They realized that they wouldn’t have to bring dissidents and critics in for trial if they could ruin their lives through more subtle means. Their strategy, called Zersetzung (‘decomposition’) used a vast database of personal information on East German citizens to engineer the destruction of reputations, failures at work, and interpersonal troubles. Stasi agents mailed sex toys to their targets’ spouses under the target’s name, made threatening and harassing phone calls, broke into homes and moved furniture in gas-lighting operations, tampered with mail; the goal was not to inflict punishment upon an insubordinate citizen, but to make that citizen lose his sense of reality, instilling doubt in every facet of his life. Stasi targets were made to feel like they were going insane, and they regularly committed suicide. Point being, a game that could produce the kinds of effects attributed to Polybius would be right up their alley. And given that the Stasi are about the closest thing to the Men in Black that definitely existed in history, I’d say that wraps up that angle pretty neatly too.

Maybe this explains the identity of the unknown person or persons went around retrieving and destroying Poly Play cabinets after the fall of the iron curtain. There certainly doesn’t seem to be any other reason why somebody would go to such trouble to recover such obsolete and relatively pointless technology. And the retrieval wasn’t a sporadic smash-and-grab thing, but a highly effective project; nobody knows exactly how many Poly Play cabinets were produced, but it seems like a low estimate would be somewhere on the order of a few hundred to a thousand. Estimates likewise vary on the number that survived the purge, but Andy’s Arcade has done the research and found no more than three cabinets that can be concretely confirmed to exist; their own game and two more, both museum exhibits.

Call me gullible or naïve if you wish, but I really think this might be it. But of course, there are less exotic possibilities, and we haven’t quite closed the loop from East Germany to Portland, Oregon, which is what we’ll tackle in the conclusion.